The authors spent a year sending each other postcards on a different theme each week, with pictorial representations of the data they had collected.

Read MoreTfL data by Terry Freedman

An article about data

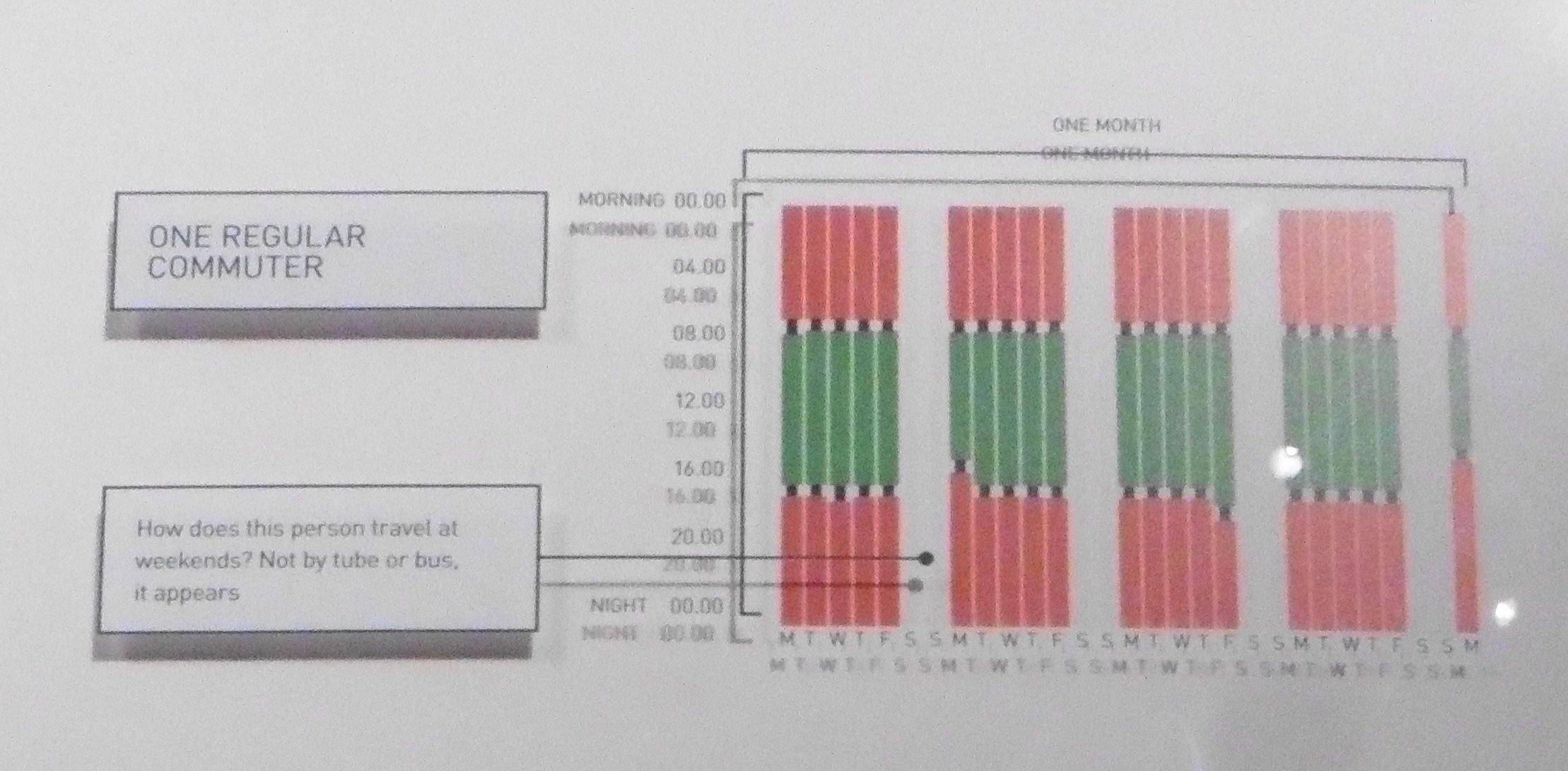

Elaine keeps telling me to remember to clock in and out at stations, even if the barriers are open. She’s right.

Read MoreCome back, Office Skills, all is forgiven?

it is clearly important to ensure that pupils understand not just the mechanics of mail-merging, but the importance of checking the data that is generated.

Read MoreOn This Day, by Terry Freedman

On this day #12: usability, assessment, tiffs, pointless data and Computing

Gosh! I don’t know if there is something special about the date December 6th — like the Ides of March, say — but I seem to have been astonishingly prolific on that date.

Read MoreHow to see the trend in students' grades at a glance

Updated! Here’s a little-known function in Google Sheets which gives you an in-cell graph. Handy for displaying trends in students' grades at a glance.

Read MoreBook review: How Charts Lie

This is a good book to read, and definitely one you’ll want in your armoury of resources.

Read MoreQualitative data is important too UPDATED

I'm a great believer in using different kinds of data to measure how well pupils are doing, not all of which are quantifiable in the usual sense.

Read MorePardon? By Terry Freedman

The usefulness of data

A technical support reporting system is only as good as the information you can extract from it.

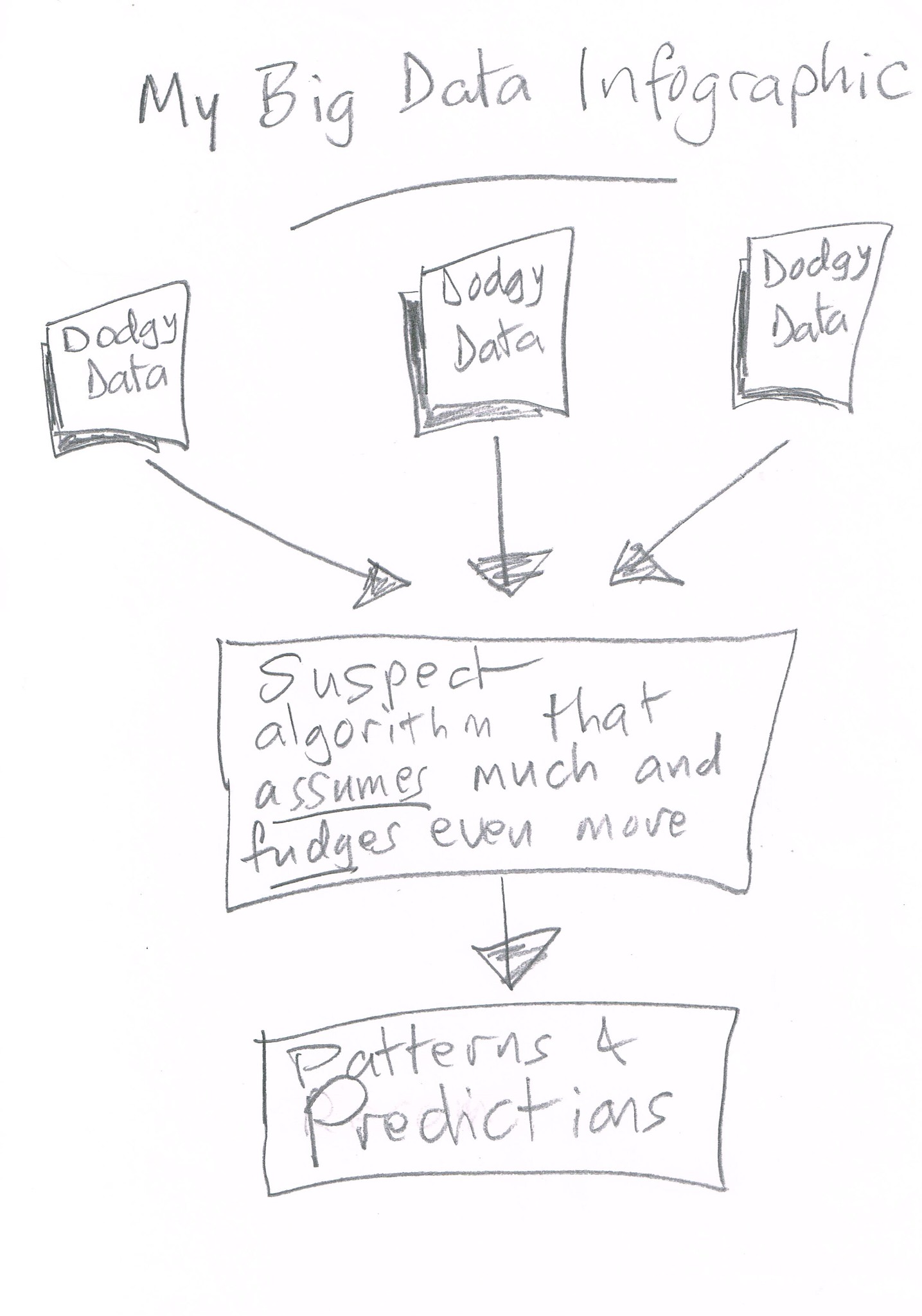

Read MoreBig Data, by Terry Freedman

Data for its own sake is pointless

Unless data can be turned into information, what’s the point of collecting it?

Read MoreQualitative data is important too

I'm a great believer in using different kinds of data to measure how well pupils are doing, not all of which are quantifiable in the usual sense.

Read MoreOur lives in data: London transport

How is your travel data used, and what the trade-offs in terms of private costs and benefits? This is the second post in a series about data and privacy, and artificial intelligence.

Read MoreBig ideas for ed tech leaders: Know your data, part 2

Big ideas for ed tech leaders: Know your data, part 1

Although I was good at statistics at university, it’s not an area that I especially warm to. However, even if terms like “grade point average” leave you cold, I think you have to collate some data to be an effective leader of education technology.

Although I was good at statistics at university, it’s not an area that I especially warm to. However, even if terms like “grade point average” leave you cold, I think you have to collate some data to be an effective leader of education technology.Awarding Levels in Computing for the purpose of number-crunching

Business emails to inspire confidence (not)

There must be a whole generation of people who know the mechanics of using technology, but have no idea of how to take charge of it. I am thinking in particular of the ridiculous marketing messages I receive, that advertise targeted marketing services. I mention this because, despite all the lambasting of “Office skills”, it is demonstrably clear that people need them. I could even make a case for this being related to digital safety. How? Reputation is important, and marketing messages that have “schoolboy errors” do nothing to enhance one’s credibility. Consider the following examples:

There must be a whole generation of people who know the mechanics of using technology, but have no idea of how to take charge of it. I am thinking in particular of the ridiculous marketing messages I receive, that advertise targeted marketing services. I mention this because, despite all the lambasting of “Office skills”, it is demonstrably clear that people need them. I could even make a case for this being related to digital safety. How? Reputation is important, and marketing messages that have “schoolboy errors” do nothing to enhance one’s credibility. Consider the following examples:Data shock

Here are three short observations on data, which may provide a basis for discussion with pupils.

Here are three short observations on data, which may provide a basis for discussion with pupils.

1. What we can learn from the Ice Age

A few weeks ago I went to the Ice Age art exhibition at the British Museum.

We are running a good service –you can see it in real time

Here’s a photo I took recently on the London Underground. There are periodic announcements, static noticeboards, and electronic delays constantly assuring us that we are experiencing a good service. I presume it is intended to introduce a feel-good element into an otherwise mundane existence.

Here’s a photo I took recently on the London Underground. There are periodic announcements, static noticeboards, and electronic delays constantly assuring us that we are experiencing a good service. I presume it is intended to introduce a feel-good element into an otherwise mundane existence.

Why should students type in data?

Is there an ICT way of thinking?

Cavalier Attitudes to Data: 5 Points and 3 Questions

I was inspired by a Westminster eForum event entitled Missing Discs and Mislaid Laptops to write this article.

Why is it that disks, data and laptops appear to go missing with alarming frequency (although, as I say in another article, this appears to have abated recently)? Is it that there is a general lack of understanding about the nature of digital data, and how it is fundamentally different from the old paper-based approach?

You may find it useful to discuss the points made in this article with your students.

We may live in the digital age physically, but mentally many people still exist in the pre-internet era. I say “still”, but this applies as much to children and young people, the so-called “digital natives”, as the rest of us. What I am referring to is the tendency to treat digitised data as merely a more convenient form of paper data. It is this failure to grasp the reality of computerised data that, in my view, underlies the alarming tendency for laptops to be left lying around and disks to be sent through the post. What it comes down to is a lack of understanding, and therefore a lack of respect.

Although people and organisations are often implored, rightly, to make backups of their data in case it is lost or deleted, there is, perhaps, not enough emphasis on the other side of the coin. That is to say, the longevity of data. Incidentally, this is a key issue to try to get across to (young) people in terms of their conduct online, especially in social networking communities. Consider the following five points.

-

Once data is computerised, the cost of duplicating it is pretty much zero, and it is easy to do. I recently read a novel in which someone unearthed sensitive documents from the WW2 era and destroyed them in order to protect people. The possibility of solving the problem in that way may or may not have been viable when the book was written; it is certainly not viable now.

-

Once data is computerised, it can be copied and copied and copied with no loss of quality. It’s not like photocopying, where after making copies of copies a certain number of times it becomes unreadable.

-

Once data is computerised, it can be spread around the world in seconds. Ask anyone who has lost their job or their reputation because of ill-advisedly sending a risqué joke to their friends by email.

-

Once something has been posted to the web, it cannot be unposted. Even if web pages are deleted, archives of them exist on the internet. You can take down a photo you have posted – but someone may have already downloaded it to their own computer and be thinking about sending it to others.

-

Encrypted data may not be as secure as you think.

When you consider these points, it becomes clear that committing data to disk, and then disseminating that information, are not trivial decisions. Organisations (and individuals) need to ask the following three questions before doing so:

1. Do we need this data, in this form? Here is a good example of this way of thinking. Because of the drive to have joined-up databases in the area of children’s services in the UK, it is often taken as read that certain data have to be available to all the professionals concerned with an individual child’s welfare. That is not necessarily true. The goal might be achieved by having a system of flags in the data, ie notes which say things like “Contact the child’s doctor about this”.

2. Have we taken basic precautionary steps to keep data safe? That means giving different people access levels according to their professional needs, as opposed to their level of seniority; making it mandatory for computers to be password-locked when people leave their desks momentarily; making it harder to pass the data on than it is to not do so.

3. What would be the cost, in terms of reputation and litigation, if we get it wrong?

Some of the issues involved can be solved by technical means, such as encryption and other security measures. But on the whole what is needed is a completely different way of looking at computerised data: a different mindset entirely.