The effects of technology on lifestyle, and techno-romanticsm

Pictures across the curriculum: After the tourists have gone

In this article, English, Economics, culture, geography and tourism are highlighted.

Like most of the pictures I take, this one was unplanned. I saw all these boats in the evening, as I crossed over the bridge in York town centre. The scene struck me as rather poignant.

But then I got to thinking, it would make a great starting point for several avenues of study, such as:

Pictures Across the Curriculum: Missing Monks

In this series I'm looking at how well-chosen digital photos can be used in different areas of the curriculum.

In this series I'm looking at how well-chosen digital photos can be used in different areas of the curriculum.

Today I'm looking a some photos that might have sparked off an historical investigation if I'd had more time.

Pictures across the curriculum: portrait of an artist

In this series I'm looking at how well-chosen digital photos can be used in different areas of the curriculum. In the first one, I looked at the problem of litter.

In this series I'm looking at how well-chosen digital photos can be used in different areas of the curriculum. In the first one, I looked at the problem of litter.

This one, however, is about a much more pleasant subject: a local artist.

I visited a beach in Suffolk recently, and came across someone painting the landscape. It was a great occasion to have my camera with me!

So who was it? Read on to find out, and to consider some possible curriculum links.

Guidance for the BETT Show (and other conferences)

Last year I published a guide to BETT (and other conferences) for subscribers to the free newsletter, Computers in Classrooms. I think the advice is still relevant. I looked at the following:

- 9 reasons to attend.

- 4 arguments to put to your boss as to why you should be allowed to attend.

- 3 other kinds of colleagues who should attend.

- 13 things to do in advance.

- 16 ways to get the most out of the show.

- 7 ways to follow up afterwards (once you’ve recovered!).

You can read that online here.

10 tips for planning the use of technology in lessons

Twitter: An evaluation

Back in August 2007 I wrote the following article about Twitter:

Back in August 2007 I wrote the following article about Twitter:

When Twitter first appeared on the scene, I thought it sounded like a complete waste of time.

But as more and people I respect started singing its praises, I thought I ought to give it a whirl.

That was a couple of months ago, and here are my conclusions.

Photographing the Curriculum

Digital cameras have been with us now for well over a decade. But three things have changed in that time.

Digital cameras have been with us now for well over a decade. But three things have changed in that time.

Firstly, you get a bigger bang for your buck, in terms of image size and quality.

Secondly, cameras on mobile phones have become good enough to mean that people can now dispense with the camera as their means of taking pictures.

C? I tld u so, didn't I? txtN isn't so bad aftr ll, unl ur /:-)

When, a few years ago, a 13 year-old girl wrote her entire English essay in texting language, people were predicting the end of civilisation as we know it. Now it turns out that research seems to suggest that texting can actually aid literacy. So where does the truth lie?

When, a few years ago, a 13 year-old girl wrote her entire English essay in texting language, people were predicting the end of civilisation as we know it. Now it turns out that research seems to suggest that texting can actually aid literacy. So where does the truth lie?

The Myth of Leadership

Leaders and managers don't change people: people change themselves. All that an effective leader or manager can do is get the right conditions in place for effective change (for the better) to happen. In political terms, it's the difference between power and authority. Power is where, when someone says "X will happen", people say "We must do X"; authority is where, when someone says "X will happen", people say "X ought to happen". Having authority is better than having power in the long run.

Leaders and managers don't change people: people change themselves. All that an effective leader or manager can do is get the right conditions in place for effective change (for the better) to happen. In political terms, it's the difference between power and authority. Power is where, when someone says "X will happen", people say "We must do X"; authority is where, when someone says "X will happen", people say "X ought to happen". Having authority is better than having power in the long run.

In Praise of Tedium

Why does everything have to be so interesting all the time? Here is my attempt to balance the scales by producing something incredibly boring.

Making It To Christmas: Starting Well

Well, the new term -- indeed, school year -- has started or is about to start, so you may think it is somewhat premature to be thinking about Christmas already!

Well, the new term -- indeed, school year -- has started or is about to start, so you may think it is somewhat premature to be thinking about Christmas already!

However, in my experience the autumn (Fall) term is the toughest of the lot, and the final few weeks can be purgatory.

Formalising meetings

Meetings should be run in a professional manner. I've written quite a bit about how to make meetings more effective and purposeful, but mainly from the perspective of the whole team. There are, however, more personal reasons to make meetings more formalised.

Meetings should be run in a professional manner. I've written quite a bit about how to make meetings more effective and purposeful, but mainly from the perspective of the whole team. There are, however, more personal reasons to make meetings more formalised.

Review of Leading a Digital School

21 Ideas for Getting Off to a Good Start

Life Without A Spellchecker

It is almost a truism that we have become too reliant on technology. You only have to step into a place where the computer system has 'gone down' to see that. Like the restaurant I wandered into a few days ago in which there was, to quote one of the staff, 'anarchy' because the computerised booking set-up had, as it were, downed tools.

But in a funny kind of way that sort of situation is copable with if you're reasonably intelligent, have a contingency plan and possess a spark of creativity. The thing is, a system which is off is, by definition, not on. Like the binary system on which it's based, the computer system's state leaves no room for doubt, no room for ambiguity. at the risk of sounding a little Monty Pythonish, it's off, not working, finished, kaput – at least for the time being.

What is far worse, in my opinion, is when something goes wrong but in such a quiet sort of way that you don't even notice at first. Thus it was that when my spell-checker stopped checking my spelling, it did so without warning, without fanfare and, crucially, without any wavy red lines. Unfortunately, the first glimmer I had of something being amiss was when I read an article I'd just posted that mentioned my being resposible.

Now there are a couple of things that come to mind about this. Firstly, it's very apparent what a shoddy job of proofreading I did. That was partly because I had implicitly assumed that the spell checker would pick up any neologism I'd 'penned'. But it was also partly because, like most people, I subconsciously substituted the correct word for the incorrect one when I was reading through my article.

That is why anyone writing for an audience on a professional basis has their work proofread by someone else. Is that done as a matter of course in schools? We harp on about writing or presenting for different audiences (in England and Wales it is stipulated in the National Curriculum). But the logical corollary of that position is having students proofread each other's work and, in special projects, splitting the task between writers and editors and proofreaders.

The second thing that strikes me, somewhat more whimsically, is that not having a spell checker is a good way of coining new words. For example, as far as I am aware the word 'resposible' does not exist (I've even looked it up in the Oxford English Dictionary), yet it sounds like it ought to. Could it be, perhaps, the property of being eligible to be taken back having been disposed of?

Inventing words accidentally, and then creating meanings for them, is quite entertaining. It goes to show that life without a spell checker, whilst not ideal, is not an entirely desperate state of affairs.

This is a slightly modified version of an article first published on 20th May 2009.

Why Teach Spreadsheets?

I often read blogs or articles which allude to the exciting nature of the possibilities of using video and podcasting in the curriculum, as opposed to spreadsheets. I think this raises a number of issues:

Firstly, why even bother to teach spreadsheets given the apparently more exciting possibilities offered by video and so on?

Secondly, is it true to say that spreadsheets are, in their very nature, boring?

Thirdly, even if they are, does it matter?

Why teach spreadsheets?

The short answer is that you don't have to. According to England and Wales' National Curriculum Programme of Study for ICT, you have to teach modelling and sequencing. You could certainly teach the latter through a curriculum centred on podcasting and other media. You could probably teach modelling too, but it would need to be thought through very carefully in order to avoid the danger of it's becoming too superficial.

Spreadsheets, however, are ideally suited to the teaching of modelling because that's exactly what they're designed to do. If you take the basic modelling question as being "What if?", using spreadsheets is, to coin an expression, a no-brainer.

But is it not the case that for spreadsheets to be useful, lots of numbers have to be involved? Well, not necessarily. I read some years ago an article by a teacher who was using spreadsheets in English to demonstrate the progression of a work of literature over time.

If, for example, you take a novel such as The Picture of Dorian Gray, you could plot the number of witticisms per chapter in a spreadsheet and then generate a graph showing how they decline as the book progresses.

Or you could take a work by Shakespeare and plot the number of jokes per scene alongside the number of killings per scene, the instances of dramatic irony per scene and anything else of interest, and then look at the resulting graph.

What that sort of thing will do is illustrate very effectively how the nature of the play or novel changes from start to finish, but it's not the only possibility. At the Online Information conference I attended in 2008 someone showed a screenshot from someone's MA thesis in which the student had used Excel to showcase the different kinds of rhyme in English poetry.

These are good examples of modelling, but you don't have to be quite so avant guard. There are lots of opportunities for modelling of the number-crunching kind, but I'll come on to those in a moment.

Let's not forget sequencing. Contrary to what some people have said, control hasn't so much disappeared from the curriculum as morphed into "sequencing", a much better term because it's more accurately descriptive and also wider in scope:

[Pupils should be able to ... ]use ICT to make things happen by planning, testing and modifying a sequence of instructions, recognising where a group of instructions needs repeating, and automating frequently used processes by constructing efficient procedures that are fit for purpose

That's exactly the kind of thing that spreadsheets are good for, which is why I decided to approach my chapter on sequencing in the latest ICT for Life (for Year 8, ie 13 year olds) through the use of a spreadsheet. It makes use of the IF function, which can be seen as a rudimentary example of sequencing, and macros, which encapsulate both sequencing and automation.

It seems to me that if you're going to decide to teach these skills through, say, video podcasting, you will have a tough time ensuring that the work is demanding enough to meet the criteria of the National Curriculum in a real, as opposed to superficial, sense.

For example, I think that it involves more than deciding on who in the class is doing what, and in what order, and then going out with a pocket camcorder and hoping for the best. You'd need to think of things like editing, which could address both sequencing and modelling, and even issues like background music (which can affect audience reactions and assumptions) as part of the attention to modelling. But, not being an expert in such matters, I think all that sounds more challenging than coming up with a good idea centred on the use of spreadsheet.

Are spreadsheets intrinsically boring?

I think if you regard a spreadsheet as little more than a glorified calculator then you would be hard put to find much of interest there. But there are two sides to the question of whether spreadsheets are boring.

Firstly, it's a matter of functionality. In a fully-featured spreadsheet like Excel, there are all sorts of ways in which you can approach "what if?" questions, from the relatively simple IF function, through conditional formatting and scenarios, to goal-seeking and pivot tables.

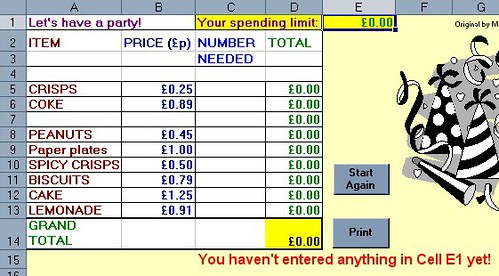

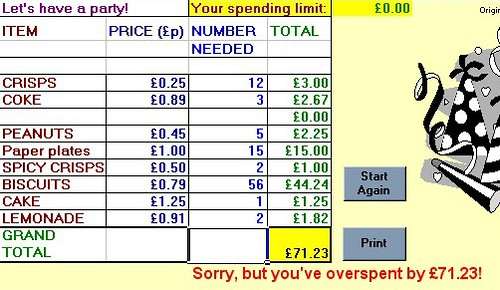

Secondly, and more importantly I think, is what you do with them. Over a decade ago I devised a spreadsheet which was quite complex behind the scenes, but easy to use. It was a party planner, and what you had to do was decide how many bottles of fizzy drink and so on you should buy. The rules were that you were not allowed to overspend or underspend (the spreadsheet would alert you if you did), and you had to buy everything on the list.

Information is provided in real-time...

Information is provided in real-time...

Obviously very simple, but put the students to work in pairs and discuss their purchases and it starts to take on a life of its own. It is actually quite hard to spend exactly a given amount of money without resorting to desperate measures like buying 200 bags of peanuts and nothing else!

Then you can start to throw in "curved balls", such as:

"Sorry, class, but I've just found out that your dad couldn't work overtime this week, so you can only spend £25 instead of £40." Or:

"Hey, I just found out that some of the people coming along are vegetarian, so make sure you buy something they can eat and drink too."

As a homework exercise beforehand you can ask them to do some research into what sorts of tings people buy for parties, and part of the lesson can involve getting onto the internet to try and find the lowest prices.

So, in a sense, the spreadsheet itself is boring: after all, all the pupils are doing is entering numbers because everything has been set up for them. But they're starting to learn what modelling is, in a way that is interesting to them.

But where this sort of approach really starts to take off is afterwards, when you say, in effect, OK, let's take the lid off and see how this thing works. You can ask the pupils, what do you think is actually happening behind the scenes to give you a message like "Sorry, but you have overspent by £14.16."?

The idea is to get them to understand the logic of what is happening, expressed in ordinary language. Once that's been achieved, you can start to construct a spreadsheet model using syntax that the spreadsheet program will understand.

If your spreadsheet work consists of (and I've seen this) getting the pupils to type in rows and rows of football scores and then find the average score and the highest score, then I agree with you: that is mind-numblingly boring. It's tedious, pointless (why not give them an already-populated spreadsheet?) and mundane.

With older students you can push the boat out a bit further. We're accustomed to spreadsheet models being concerned with business or sports, but how about science fiction for a change?

In The Cold Equations, Tom Godwin posits the idea of a supply spaceship that has almost precisely the right amount of fuel for its return journey, taking into account weight and distance. What happens when the pilot discovers a stowaway on board? I won't spoil the story for you by telling you (read it, especially if part of your job is to discuss moral issues with your students), but what a great starting point for a spreadsheet exercise! Can you construct a simple model showing what happens to fuel consumption when one of the critical factors (weight or distance) goes over a certain limit?

Again, this activity can be enriched by asking the pupils to do research into this area -- not necessarily in the area of space flight, but in the more accessible realm of fuel consumption by cars.

Even if spreadsheet are boring, does it matter?

I thought I'd throw this one in. I do think it matters, up to a point, which is why I wrote the book "Go on: bore 'em: how to make ICT lessons excruciatingly dull". However, I do think there is a danger of falling into the trap of thinking that school has to be entertaining all the time. It's a fact of life that some activities are boring, but possibly necessary.

What springs immediately to my mind is preparing my invoices. I love the work I do, and when I finish one assignment I like to move on to the next. Instead, I have to find time to sort out the paperwork and get an invoice sent off to the client. That's just plain boring as far as I'm concerned. But if I didn't do it, we wouldn't eat!

I'm not suggesting that we try and bore kids as part of their preparation for adult life! But neither do I think we should tear our hair out and rent our clothes if school activities are not always as action-packed and fun-filled as kids would often have us believe they want them to be.

In fact, it's a con on their part, perhaps an inadvertent one. What kids want at school is not necessarily to be entertained, but to be kept interested, and to feel that they're learning something useful. Spreadsheets have the potential to form the basis of activities that help to achieve exactly those goals.

This is an updated version of an article that was first published on 24th December 2008.

Risk Assessment

You cannot avoid risk, so you have to manage it. Whether you’re considering installing a new computer system, or trying out a new teaching approach, how can you manage the risk sensibly and effectively?

You have to manage riskThe way to do so is to carry out a risk assessment. That sounds like it could be a lot of work, but it need not be. Or at least, it can be turned into an enjoyable professional development exercise. That way, not only do you assess the risk, you also (hopefully) bring your colleagues along with you and, into the bargain, have some mind-stretching discussions as part of the process.

You have to manage riskThe way to do so is to carry out a risk assessment. That sounds like it could be a lot of work, but it need not be. Or at least, it can be turned into an enjoyable professional development exercise. That way, not only do you assess the risk, you also (hopefully) bring your colleagues along with you and, into the bargain, have some mind-stretching discussions as part of the process.

The reason for that is simple: risk assessment tends to be fairly subjective. You can make it less so by doing some research and obtaining a range of facts and figures, but ultimately you have to take a decision, and that will involve a degree of conjecture.

Risk assessment involves considering, and assigning values to, three criteria:

- What can happen as a result of this course of action?

- What is the likelihood of each outcome happening?

- How bad will be the consequences of each thing happening?

Now, in some scenarios the value assigned to the last one is so great that it crowds out any other consideration. For example, what is the likelihood of your child being abducted if you allow her to go out on her own? The answer, despite what you may think from keeping up with the daily news, is quite low in the UK. However, the consequences of that happening would be so awful as to render the low likelihood irrelevant.

Thankfully, when it comes to trying out innovative teaching methods we tend not to have to countenance such extreme situations. So, let’s work through an example:

Question: What might happen if I introduce the use of social networking into my lessons?

You might set out a grid like this:

|

Outcome |

Likelihood of occurring |

Severity of consequences |

| Students will fail course | Low | High |

| Parents will complain | Medium | Medium |

| Students will come across unsavoury people | High | High |

Now, you can start to manage all this. For example, taking the last one, you can prepare the students by teaching them about keeping safe online, and you can further protect them by having an invitation-only social network. That won’t completely protect them (if only because some of the students may themselves be unsavoury characters), but it will certainly go a long way towards reducing the risks.

But the important thing to bear in mind about risk is that once you have identified an activity as potentially ‘risky’, the solution is not necessarily to simply abandon the idea. After all, keeping to ‘tried and true’ teaching methods also carries a risk.

An earlier version of this article was published on 11th June 2009.

5 Tips For Assessing What Students Know

It is not enough to teach students how to understand information and communications technology. At some point you are going to have to assess their knowledge and understanding.

Girl studying. (c) hvaldez1 (http://www.sxc.hu/profile/hvaldez1)Here are 5 broad suggestions of how to do so effectively.

Girl studying. (c) hvaldez1 (http://www.sxc.hu/profile/hvaldez1)Here are 5 broad suggestions of how to do so effectively.

1. Set open-ended tasks rather than closed tasks

For example, say: “Produce a poster” rather than “Produce a poster using Microsoft Publisher”. By the same token, don't be too prescriptive in what needs to be included. Instructions like "include 2 pieces of clip-art" do not easily lend themselves to assessment of much more than the student's ability to select appropriate illustrations. In fact, such a painting-by-numbers approach may be useful as a training exercise, but ultimately all you can really assess is how good the students are at following instructions.

The open-ended approach can be adapted for use with all age groups, in my experience.

2. Use a problem-solving approach rather than a skills-based approach

This suggestion assumes that the course is a problem-solving one rather than once concerned purely with skills. In some circumstances it will be quite appropriate to ask students, say, to create a spreadsheet consisting of 5 worksheets and involving the use of the IF function. However, for the sorts of courses I'm thinking about, a question that requires problem-solving is much better, for these reasons:

- It does not require there to be one right answer.

- It provides an opportunity to discuss with the student why they opted for a particular solution -- and why they did not choose an obvious alternative.

- It provides scope for out-of-the-box thinking. The trouble with telling students they must (to continue with the example) use an IF function precludes them from coming up with a more creative, and potentially better, solution of their own.

3. Watch what students do in the lesson

The finished product indicates very little about ICT capability. In the absence of other information, it’s the process that counts. The biggest problem with making a statement like this is that teachers and others can sometimes extrapolate from it to suggest that the process is all that matters. This is patently not the case, as a simple example will illustrate:

Your boss asks you to prepare a presentation on the subject of what the school offers by way of ed tech facilities, to be shown to prospective parents at a forthcoming Open Day. You prepare a fantastic presentation, using all the bells and whistles (appropriately, of course), on the topic of what ed tech facilities the school will offer in 5 years' time once an impending refurbishment programme has been completed.

The way you prepared it is sheer brilliance: you create an outline in a word processor, import it into a presentation program in a way that automatically creates slides and bullet points, and all your illustrations are original, created by you and your students.

Given the fact that your presentation is actually irrelevant, or at least not what the boss asked for, how likely is it that your boss will congratulate you on your presentation on the grounds that the way you went about preparing it was exemplary?

4. Avoid the temptation to atomise

Do not disassemble the Level Descriptors in the National Curriculum Programme of Study (in England and Wales), or, indeed, any set of national standards. The English and Welsh ones are intended as holistic descriptions rather than atomistic ones, and it is likely that the same is true of other countries' standards (but you will need to verify that, of course).

5. Assess what students say about the work they have done

You may find it useful to use a standardised approach, but I have always found that you can pick up a lot from a fairly open-ended discussion. It's interesting to explore, for example, if they understand why they have done something. (An answer along the lines of "Because the teacher told me to" is not good enough.)

This article was first published on 2nd January 2008.