Also on the web: 08/05/2010 (p.m.)

-

Let’s Say No to Inappropriate Use of Technology

Another timely, thought-provoking (and somewhat long) post, about the inappropriate use of technology in education. In my view, it's essential that people know when NOT to use technology. Read the post, decide for yourself.

Posted from Diigo. The rest of my favorite links are here.

The Case For Homework in ICT

Should homework be set for ICT lessons? A common argument against the idea is that it’s unfair on those students who don’t have access to computers outside school. My answer to that is: set homework which doesn’t need access to a computer.

Homework can be fun too! © cienpies.net http://fotos.cienpies.net/I suspect that much of the antipathy I’ve encountered towards setting homework is that it smacks of traditionalism. The very idea of homework is, in this sense, the antithesis of all we ed tech people like to believe we stand for: cutting edge, innovative – if not digital natives, then at least digital explorers.

Homework can be fun too! © cienpies.net http://fotos.cienpies.net/I suspect that much of the antipathy I’ve encountered towards setting homework is that it smacks of traditionalism. The very idea of homework is, in this sense, the antithesis of all we ed tech people like to believe we stand for: cutting edge, innovative – if not digital natives, then at least digital explorers.

I don’t see that at all. Homework can be used to ensure that the work in the classroom proceeds as quickly and as smoothly as possible. If much of your teaching style involves project work, then why not set a generic homework like: Do whatever you need to do in order to work effectively on your project next lesson? To make that work, it’s a good idea to ensure that the last five or ten minutes of the lesson is given over to identifying what has been achieved and what are the next steps. That way, students can see for themselves that they will need to, say, find out local supermarket prices in order to create an advertisement for a new product.

There is another reason for setting homework. If you work in a school in which homework is expected to be set, then by not setting it for ICT you’re declaring, in effect, ICT to be a non-subject. Non-subjects don’t get timetable time. Non-subjects don’t get first refusal when unexpected funds become available. Non-subjects don’t get much more than subsistence capitation (budget).

So for both political (with a small ‘p’) reasons and educational ones, homework in ICT is absolutely necessary. As The Commodores said in “Slippery When Wet”:

Having fun ain’t no good, leaving homework undone!

Life Without A Spellchecker

It is almost a truism that we have become too reliant on technology. You only have to step into a place where the computer system has 'gone down' to see that. Like the restaurant I wandered into a few days ago in which there was, to quote one of the staff, 'anarchy' because the computerised booking set-up had, as it were, downed tools.

But in a funny kind of way that sort of situation is copable with if you're reasonably intelligent, have a contingency plan and possess a spark of creativity. The thing is, a system which is off is, by definition, not on. Like the binary system on which it's based, the computer system's state leaves no room for doubt, no room for ambiguity. at the risk of sounding a little Monty Pythonish, it's off, not working, finished, kaput – at least for the time being.

What is far worse, in my opinion, is when something goes wrong but in such a quiet sort of way that you don't even notice at first. Thus it was that when my spell-checker stopped checking my spelling, it did so without warning, without fanfare and, crucially, without any wavy red lines. Unfortunately, the first glimmer I had of something being amiss was when I read an article I'd just posted that mentioned my being resposible.

Now there are a couple of things that come to mind about this. Firstly, it's very apparent what a shoddy job of proofreading I did. That was partly because I had implicitly assumed that the spell checker would pick up any neologism I'd 'penned'. But it was also partly because, like most people, I subconsciously substituted the correct word for the incorrect one when I was reading through my article.

That is why anyone writing for an audience on a professional basis has their work proofread by someone else. Is that done as a matter of course in schools? We harp on about writing or presenting for different audiences (in England and Wales it is stipulated in the National Curriculum). But the logical corollary of that position is having students proofread each other's work and, in special projects, splitting the task between writers and editors and proofreaders.

The second thing that strikes me, somewhat more whimsically, is that not having a spell checker is a good way of coining new words. For example, as far as I am aware the word 'resposible' does not exist (I've even looked it up in the Oxford English Dictionary), yet it sounds like it ought to. Could it be, perhaps, the property of being eligible to be taken back having been disposed of?

Inventing words accidentally, and then creating meanings for them, is quite entertaining. It goes to show that life without a spell checker, whilst not ideal, is not an entirely desperate state of affairs.

This is a slightly modified version of an article first published on 20th May 2009.

The Case For Word Puzzles

Word puzzles have a place in the ICT teacher's armoury. On the face of it, that sounds like a ridiculous statement: how can a word search, say, or a crossword, be of any use to pupils?

It seems to me that word puzzles represent a very good way of engaging learners. I think this applies especially to certain types of children, the ones for whom concentrating for longer than ten minutes is a challenge, and paragraphs of text a barrier.

A word puzzle may be used as a way of reinforcing the terminology associated with a particular topic, or of gently testing the pupils on their grasp of the relevant vocabulary.

You can also go further in respect of the latter by asking pairs of pupils to create their own word puzzles on a particular topic.

Thanks to technology, creating puzzles is no longer the labour-intensive and time-consuming activity it once was. I like the menu of options available on the Discovery Education Puzzlemaker site, for example, and it must have taken me all of three minutes to create the wordsearch puzzle below, on the subject of digital safety.

R E P O R T F G K Y M A C Y T

U C K G N X L P F Q Q Y F T H

H P A R G O T O H P B E Y I E

U N R P H R I L X E R C W T F

E A R C Z L I T R R A Y O N T

A P D D D H O B C V A N H E K

G Q O V I R U X I E P Q A D M

J G Y C T L S R Y O T P A I P

D U E D L L P H O M A O Z K J

E O G Y M Q B A T A D H R P T

P J I U G S C Y Y Z H C U P B

B N W P M L C F R I M P U L U

G P V Y P N H A N O W J L H S

P Q U F M U A T H P N E O H P

M C K A A V I F K P O Z X A U

AUP

BYRON

CEOP

CYBERBULLYING

DATA

IDENTITY

PHOTOGRAPH

PRIVACY

PROTECTION

REPORT

THEFT

You can have it generated as text or HTML, and obtain the solution as well. Other types of word puzzle are also available. I'd recommend supplementing the puzzle by asking the pupils to do something extra, such as write meaningful sentences which incorporate the words used.

Used sensibly, creatively and as part of an array of resources, word puzzles can supplement your teaching very well.

See also The Power of Words.

In The Picture: History Lesson

Here’s a photo that was taken circa 1990. It shows a history lesson in progress, in one of the computer rooms. This is the sort of lesson I really like. As you can tell from looking at the picture, which was unposed, all the kids are fully engaged. The history teacher can be seen to the left of the photo, almost out of shot – literally a guide on the side. The topic, as you may have gathered, is the assassination of President John F. Kennedy, and the students, who were 14 at the time, were using a variety of sources, both digital and paper.

I’ve annotated the photo with letters. Here’s what they indicate.

A: The history teacher.

B Two girls collaborating on researching a database.

C Girl making notes on her findings, on paper, for use in a presentation later.

D Screenshots from the JFK database showing photos that were taken at the time.

E You can’t see it very well, but that’s a box of printer paper for use in a dot matrix printer. The paper was a ream of pages joined up and perforated, like toilet paper, with sprocket holes down the sides.

F A camera. I used to use cameras in my lessons to capture what went on. Note that this was pre-digital camera days, so the camera took…

G … Film.

H Newspapers, just one of several types of resources we used in the lesson.

I It’s not very clear, but that’s a 3.5” so-called “floppy disk”. That one could hold around 740 kilobytes of data.

J A monitor. It looks very quaint now, but I’d equipped the room with Atari ST computers. Although mainly associated with games, there was a range of office and educational applications available. All the programs shared common menus, which made it very easy to learn new applications – remember, this was around the time of Windows version 1. The monitors were high definition, with black text on a white background, unlike certain other computers at the time. They were fast too.

K As far as I can tell, this is one of only two girls in the entire class who was actually listening to the teacher at the time; well, be fair: they had work to do!

If you think I’ve missed some bits which need explaining, please let me know.And please let me know if you find this sort of thing interesting.

The Reform Symposium Conference

What a weekend! From Friday to Sunday, the Reform Symposium Conference was in full swing (apart from the scheduled breaks, of course). A truly international conference, it not only featured presenters and enjoyed participation from all over the world, the organisers planned it such that events started at convenient times for people all over the globe. That made a nice change from having to stay up half the night to catch every session!

Unfortunately, I was able to attend only a few sessions, because a malignant Fate, to use a phrase much-loved by Dornford Yates, decreed that my plans to work on Monday and Tuesday had to be brought forward to Sunday instead. The sessions I did attend were interesting. I especially liked one by Nicholas Provenzano called Everything I Learned About Tech Integration I Learned From Movies. I had to leave part of the way through, but it looked like an innovative approach to talking about educational technology, taking quotations from films and applying them in a new context.

Lisa Dabbs and Joan Young gave a practical talk called New Teacher Survival Kit, which I think should be essential viewing for anyone working with new teachers. I was slightly concerned when the whole focus seemed to be on being positive in a positive kind of way. What I mean is, I sometimes think that the most positive thing you can do is tell someone they’re mistaken, and in my experience there are some people who don’t get the key message if you package it up with lots of nice fluffy compliments. So I was pleased that Joan’s response, when I raised it as an issue, was to pretty much agree.

Steve Hargadon opened the conference with an interesting keynote about social media in education, and this was followed by a talk by George Couros called Identity Day: Revealing the Passions of Our Students, which basically said that in order to teach effectively you have to know your students. Absolutely. Teaching, like business and any other human transaction, is ultimately based on relationships.

I was honoured to have been invited to give a keynote, and spoke about using a project management approach to introducing Web 2.0 into your classroom.

The sessions were all recorded, and should eventually be available for viewing – some are there already, but others may take around a week. Go here for the schedule, and click on the link in the column called Webinar Link for the session you wish to view. I intend to look at all of them.

Top marks to the organisers Shelly Terrell, Christopher Rogers, Jason Bedell and Kelly Tenkely and their team of moderators for their tireless efforts, advanced planning and attention to detail. The odd glitch was handled deftly and virtually without anyone noticing. I was especially gratified when Phil Hart got my slides going despite some horrible error messages I kept getting whilst trying to upload the PowerPoint. Thanks also to my friend Peggy George, who took time out to show me some of the functionality of Elluminate, as it had been a while since I’d used it.

Finally, it was a nice touch to give presenters a certificate. You can see mine here.

Remember: check out the presentations! Whilst looking at them, think about whether they could be useful for you when running a CPD session. Don’t ignore the chat window: as is often the case, what’s going on in the chat is an interesting complement to the presentation proper.

Why Do You Blog?

In Why I Write, George Orwell suggests the following reasons that someone may wish to write:

- To make money.

- Egoism, eg a desire to appear clever, or to be remembered after your death.

- Aesthetic enthusiasm, eg a love of words for their own sake.

- Historical impulse, ie a desire to see things as they really are, so that posterity my benefit.

- Political (with a small ‘p’), ie to influence other people’s ideas about society.

I’d also add another two:

Educational, ie the desire to give others the benefit of the knowledge you’ve acquired – which I suppose could also come under the heading of egoism, or even political.

Record-keeping, be that as a diary, a research record, or another kind of journal.

So I am wondering if these categories might be applied to blogging? Why do people blog? I’ve set up a very simple, and no doubt simplistic, poll to find out. I know the categories are subtle and overlap and interface with each other. Nevertheless, my poll comprises just one question:

What is your number one reason for blogging?

Do take part, and feel free to add reasons of your own on the ‘Other’ category. Let’s see what transpires.

Why Teach Spreadsheets?

I often read blogs or articles which allude to the exciting nature of the possibilities of using video and podcasting in the curriculum, as opposed to spreadsheets. I think this raises a number of issues:

Firstly, why even bother to teach spreadsheets given the apparently more exciting possibilities offered by video and so on?

Secondly, is it true to say that spreadsheets are, in their very nature, boring?

Thirdly, even if they are, does it matter?

Why teach spreadsheets?

The short answer is that you don't have to. According to England and Wales' National Curriculum Programme of Study for ICT, you have to teach modelling and sequencing. You could certainly teach the latter through a curriculum centred on podcasting and other media. You could probably teach modelling too, but it would need to be thought through very carefully in order to avoid the danger of it's becoming too superficial.

Spreadsheets, however, are ideally suited to the teaching of modelling because that's exactly what they're designed to do. If you take the basic modelling question as being "What if?", using spreadsheets is, to coin an expression, a no-brainer.

But is it not the case that for spreadsheets to be useful, lots of numbers have to be involved? Well, not necessarily. I read some years ago an article by a teacher who was using spreadsheets in English to demonstrate the progression of a work of literature over time.

If, for example, you take a novel such as The Picture of Dorian Gray, you could plot the number of witticisms per chapter in a spreadsheet and then generate a graph showing how they decline as the book progresses.

Or you could take a work by Shakespeare and plot the number of jokes per scene alongside the number of killings per scene, the instances of dramatic irony per scene and anything else of interest, and then look at the resulting graph.

What that sort of thing will do is illustrate very effectively how the nature of the play or novel changes from start to finish, but it's not the only possibility. At the Online Information conference I attended in 2008 someone showed a screenshot from someone's MA thesis in which the student had used Excel to showcase the different kinds of rhyme in English poetry.

These are good examples of modelling, but you don't have to be quite so avant guard. There are lots of opportunities for modelling of the number-crunching kind, but I'll come on to those in a moment.

Let's not forget sequencing. Contrary to what some people have said, control hasn't so much disappeared from the curriculum as morphed into "sequencing", a much better term because it's more accurately descriptive and also wider in scope:

[Pupils should be able to ... ]use ICT to make things happen by planning, testing and modifying a sequence of instructions, recognising where a group of instructions needs repeating, and automating frequently used processes by constructing efficient procedures that are fit for purpose

That's exactly the kind of thing that spreadsheets are good for, which is why I decided to approach my chapter on sequencing in the latest ICT for Life (for Year 8, ie 13 year olds) through the use of a spreadsheet. It makes use of the IF function, which can be seen as a rudimentary example of sequencing, and macros, which encapsulate both sequencing and automation.

It seems to me that if you're going to decide to teach these skills through, say, video podcasting, you will have a tough time ensuring that the work is demanding enough to meet the criteria of the National Curriculum in a real, as opposed to superficial, sense.

For example, I think that it involves more than deciding on who in the class is doing what, and in what order, and then going out with a pocket camcorder and hoping for the best. You'd need to think of things like editing, which could address both sequencing and modelling, and even issues like background music (which can affect audience reactions and assumptions) as part of the attention to modelling. But, not being an expert in such matters, I think all that sounds more challenging than coming up with a good idea centred on the use of spreadsheet.

Are spreadsheets intrinsically boring?

I think if you regard a spreadsheet as little more than a glorified calculator then you would be hard put to find much of interest there. But there are two sides to the question of whether spreadsheets are boring.

Firstly, it's a matter of functionality. In a fully-featured spreadsheet like Excel, there are all sorts of ways in which you can approach "what if?" questions, from the relatively simple IF function, through conditional formatting and scenarios, to goal-seeking and pivot tables.

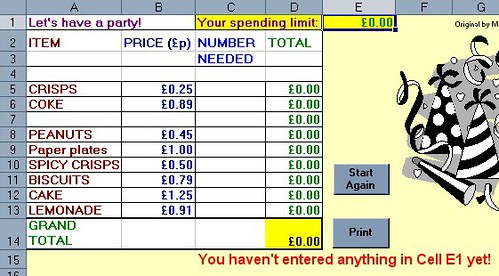

Secondly, and more importantly I think, is what you do with them. Over a decade ago I devised a spreadsheet which was quite complex behind the scenes, but easy to use. It was a party planner, and what you had to do was decide how many bottles of fizzy drink and so on you should buy. The rules were that you were not allowed to overspend or underspend (the spreadsheet would alert you if you did), and you had to buy everything on the list.

Information is provided in real-time...

Information is provided in real-time...

Obviously very simple, but put the students to work in pairs and discuss their purchases and it starts to take on a life of its own. It is actually quite hard to spend exactly a given amount of money without resorting to desperate measures like buying 200 bags of peanuts and nothing else!

Then you can start to throw in "curved balls", such as:

"Sorry, class, but I've just found out that your dad couldn't work overtime this week, so you can only spend £25 instead of £40." Or:

"Hey, I just found out that some of the people coming along are vegetarian, so make sure you buy something they can eat and drink too."

As a homework exercise beforehand you can ask them to do some research into what sorts of tings people buy for parties, and part of the lesson can involve getting onto the internet to try and find the lowest prices.

So, in a sense, the spreadsheet itself is boring: after all, all the pupils are doing is entering numbers because everything has been set up for them. But they're starting to learn what modelling is, in a way that is interesting to them.

But where this sort of approach really starts to take off is afterwards, when you say, in effect, OK, let's take the lid off and see how this thing works. You can ask the pupils, what do you think is actually happening behind the scenes to give you a message like "Sorry, but you have overspent by £14.16."?

The idea is to get them to understand the logic of what is happening, expressed in ordinary language. Once that's been achieved, you can start to construct a spreadsheet model using syntax that the spreadsheet program will understand.

If your spreadsheet work consists of (and I've seen this) getting the pupils to type in rows and rows of football scores and then find the average score and the highest score, then I agree with you: that is mind-numblingly boring. It's tedious, pointless (why not give them an already-populated spreadsheet?) and mundane.

With older students you can push the boat out a bit further. We're accustomed to spreadsheet models being concerned with business or sports, but how about science fiction for a change?

In The Cold Equations, Tom Godwin posits the idea of a supply spaceship that has almost precisely the right amount of fuel for its return journey, taking into account weight and distance. What happens when the pilot discovers a stowaway on board? I won't spoil the story for you by telling you (read it, especially if part of your job is to discuss moral issues with your students), but what a great starting point for a spreadsheet exercise! Can you construct a simple model showing what happens to fuel consumption when one of the critical factors (weight or distance) goes over a certain limit?

Again, this activity can be enriched by asking the pupils to do research into this area -- not necessarily in the area of space flight, but in the more accessible realm of fuel consumption by cars.

Even if spreadsheet are boring, does it matter?

I thought I'd throw this one in. I do think it matters, up to a point, which is why I wrote the book "Go on: bore 'em: how to make ICT lessons excruciatingly dull". However, I do think there is a danger of falling into the trap of thinking that school has to be entertaining all the time. It's a fact of life that some activities are boring, but possibly necessary.

What springs immediately to my mind is preparing my invoices. I love the work I do, and when I finish one assignment I like to move on to the next. Instead, I have to find time to sort out the paperwork and get an invoice sent off to the client. That's just plain boring as far as I'm concerned. But if I didn't do it, we wouldn't eat!

I'm not suggesting that we try and bore kids as part of their preparation for adult life! But neither do I think we should tear our hair out and rent our clothes if school activities are not always as action-packed and fun-filled as kids would often have us believe they want them to be.

In fact, it's a con on their part, perhaps an inadvertent one. What kids want at school is not necessarily to be entertained, but to be kept interested, and to feel that they're learning something useful. Spreadsheets have the potential to form the basis of activities that help to achieve exactly those goals.

This is an updated version of an article that was first published on 24th December 2008.

The Art of Stating the Obvious

Do advertisers know something we don’t? Some years ago a soft drinks company brandished the slogan “Our bottles are sterilised with steam!” – omitting the fact that all soft drinks companies used that method. I was reminded of this yesterday whilst in a hardware store (the old kind of hardware, ie nuts and bolts and things). On sale was a fly swat whose packaging proudly declared: “Poison-free”. That’s right: there wasn’t even an exclamation mark, which would at least have hinted at self-irony.

Tell me something I DON'T knowHave ICT Co-ordinators and others whose job it is to bring other colleagues on board with using technology missed a trick? Perhaps posters could inform people that computers do things automatically, or that word processors have built-in spell-checkers.

Tell me something I DON'T knowHave ICT Co-ordinators and others whose job it is to bring other colleagues on board with using technology missed a trick? Perhaps posters could inform people that computers do things automatically, or that word processors have built-in spell-checkers.

Actually, I know I’m being slightly cynical, but on a serious point, where do you draw the line? For example, I am pretty sure that a lot of people don’t realise that spreadsheets let you run the same basic calculation over and over again without your having to enter all the information again – unlike with a calculator, once you have set the spreadsheet up all you have to do is change the numbers (variables) you use.

I’m fairly confident that most people know that spell-checkers are a feature of word-processors, but what about the outlining feature, which allows you to see only the main headings? And if aware of that, are they further aware that by changing the order of those headings, they will automatically move all the text under them?

People don’t know what they don’t know. It may be worthwhile trying to think of things your colleagues don’t know about the computer facilities in your school – and then telling them all about what, to you, is obvious.

5 Tips For Assessing What Students Know

It is not enough to teach students how to understand information and communications technology. At some point you are going to have to assess their knowledge and understanding.

Girl studying. (c) hvaldez1 (http://www.sxc.hu/profile/hvaldez1)Here are 5 broad suggestions of how to do so effectively.

Girl studying. (c) hvaldez1 (http://www.sxc.hu/profile/hvaldez1)Here are 5 broad suggestions of how to do so effectively.

1. Set open-ended tasks rather than closed tasks

For example, say: “Produce a poster” rather than “Produce a poster using Microsoft Publisher”. By the same token, don't be too prescriptive in what needs to be included. Instructions like "include 2 pieces of clip-art" do not easily lend themselves to assessment of much more than the student's ability to select appropriate illustrations. In fact, such a painting-by-numbers approach may be useful as a training exercise, but ultimately all you can really assess is how good the students are at following instructions.

The open-ended approach can be adapted for use with all age groups, in my experience.

2. Use a problem-solving approach rather than a skills-based approach

This suggestion assumes that the course is a problem-solving one rather than once concerned purely with skills. In some circumstances it will be quite appropriate to ask students, say, to create a spreadsheet consisting of 5 worksheets and involving the use of the IF function. However, for the sorts of courses I'm thinking about, a question that requires problem-solving is much better, for these reasons:

- It does not require there to be one right answer.

- It provides an opportunity to discuss with the student why they opted for a particular solution -- and why they did not choose an obvious alternative.

- It provides scope for out-of-the-box thinking. The trouble with telling students they must (to continue with the example) use an IF function precludes them from coming up with a more creative, and potentially better, solution of their own.

3. Watch what students do in the lesson

The finished product indicates very little about ICT capability. In the absence of other information, it’s the process that counts. The biggest problem with making a statement like this is that teachers and others can sometimes extrapolate from it to suggest that the process is all that matters. This is patently not the case, as a simple example will illustrate:

Your boss asks you to prepare a presentation on the subject of what the school offers by way of ed tech facilities, to be shown to prospective parents at a forthcoming Open Day. You prepare a fantastic presentation, using all the bells and whistles (appropriately, of course), on the topic of what ed tech facilities the school will offer in 5 years' time once an impending refurbishment programme has been completed.

The way you prepared it is sheer brilliance: you create an outline in a word processor, import it into a presentation program in a way that automatically creates slides and bullet points, and all your illustrations are original, created by you and your students.

Given the fact that your presentation is actually irrelevant, or at least not what the boss asked for, how likely is it that your boss will congratulate you on your presentation on the grounds that the way you went about preparing it was exemplary?

4. Avoid the temptation to atomise

Do not disassemble the Level Descriptors in the National Curriculum Programme of Study (in England and Wales), or, indeed, any set of national standards. The English and Welsh ones are intended as holistic descriptions rather than atomistic ones, and it is likely that the same is true of other countries' standards (but you will need to verify that, of course).

5. Assess what students say about the work they have done

You may find it useful to use a standardised approach, but I have always found that you can pick up a lot from a fairly open-ended discussion. It's interesting to explore, for example, if they understand why they have done something. (An answer along the lines of "Because the teacher told me to" is not good enough.)

This article was first published on 2nd January 2008.

It’s About The Kids, Isn’t It?

GraphicaGirl is absolutely right when she says, referring to my article about Mission Statements (or see this Anglicised version):

We, in education, are in the kid business, and too often we get caught up in the day-to-day operations of the school and forget that bit.

They're what it's all about!She goes on to say:

They're what it's all about!She goes on to say:

Our business is kids, no matter how trite that may sound!

Exactly right: it is true (and it does sound trite, but what can one do?)

If you ever have occasion to visit a great bastion of education, not necessarily a school, have a look at the displays. Are there any pictures of youngsters? I think the answer can tell you quite a lot about the organisation.

See also:

What I look for in a conference

7 Tips for Planning an ICT Lesson with One or Two Computers

What if you can only have access to one or two computers for the whole class for much of the time. Does that mean you cannot do anything of any value? Not at all. Here are seven suggestions for how to make the best of the situation.

Draw up a class rota of who will be using the computer(s), and in which lesson. Your planning may not entirely work out in practice, because of factors like absences and power cuts and so on. However, it is easier to ensure that all pupils have been given the same opportunities to use the computers if you have a rota than if you don’t.

With the ICT co-ordinator or other teachers, identify the areas of the ICT Programme of Study (PoS) -- or your own scheme of work -- that you will be able to cover. This is not to say that the ICT PoS is a sort of pick-’n’-mix, but that it may be possible for different teachers to cover different aspects of the PoS in order to ensure that it is completely covered.

Devise generic activities that can be applied to a variety of situations, such as internet research skills and copy/paste.

Devise activities that require pupils to share a computer. Computers are excellent for encouraging collaborative learning and higher-order skills such as modelling.

Adopt the approach of showing the pupils as a class how to do something on the computer, and then practising it in that lesson and subsequent lessons.

Plan your lessons in a way that computer-based work and non-computer-based work are similar in terms of intended learning outcomes. For example, to take the copying and pasting idea again, all pupils could be engaged in finding suitable pictures and pasting them into their written work, whether they are working at a computer or not.

If you are in the fortunate position of having a computer suite and computers in classrooms, it may be possible to teach the whole class a computer skill all at once, which they can subsequently practice in the context of other subjects and/or lessons.

Did you find this article helpful or useful? It was first published on 15th February 2008.

Let Them Ask

Doug Woods looks at how technology can help learners ask questions.

Doug Woods looks at how technology can help learners ask questions.

Asking questions is very much a part of the learning process and there are ways in which we can use educational technology to support this. It is surprising therefore to see that the way questioning is handled in schools and colleges seems to have changed little in the last fifty years. Up and down the country, you will still see learners asking questions by first raising their hand and waiting for the teacher to acknowledge them. Is this the best way?

The first problem with having to raise your hand to ask a question is that you have to be physically present and make yourself visible to the professional (teacher, lecturer, etc.) leading the session. So what happens if the question occurs to you when doing homework or revising? What happens if you are absent and/or accessing the session remotely? In such circumstances, simply raising your hand is not an option and the ability to ask your question could be lost.

Then there are some sessions or lessons where you feel you can only ask questions at a certain time; usually at the end. A question may occur to you during a session but, when the lecturer finishes by asking ‘does anyone have any questions?' you find you've forgotten what it was! Or maybe you can remember it but there are so many other people asking questions that you do not get time to ask yours. Then, of course, there are those times when you want to ask your question at the end but you know that you, and everyone else, are simply dying to get away, so you stay quiet.

There are also times when a question occurs to you after the session. Perhaps you've been thinking about the session afterwards and something occurs to you, or maybe you read something elsewhere, which leads you to question something you heard, or thought you heard, during the session. How then could you ask your question? Maybe you experience something, perhaps from some practical work related to the session, which doesn't quite fit with what was mentioned in the session, how can you raise this?

Then there are those times when you want to ask a question of one of your fellow learners. How can you do that in a session if all your attention is directed toward the teacher/lecturer?

I daresay we can all relate to instances such as these, or we can recall times when we were dying to ask a question and, for some reason, didn't. Speaking for myself, I know that I cannot put my hand on my heart and say that every question I didn't ask would have been a serious one. Furthermore, I cannot be certain that, by not asking the question, I missed out on some new information or level of understanding. There is always the possibility, though, that had I asked the question(s) I wanted to, my level of attainment could have been better.

Having established the importance of asking questions and set out some of the traditional difficulties of doing so, we have to ask ‘how can educational technology help learners ask their questions?'

Ideally, I suppose we could be looking for a piece of technology, which could be used during a session and afterwards, for a piece of technology that can be used equally by those attending the session as well as those absent or accessing the session remotely. This piece of technology would need to be accessible and available to all, so that questions and answers can be shared and so that no advantage is given to certain users but not others.

There could be several possible solutions but one which I'd like to put forward is the use of online discussion forums. What I'd like to suggest is that every subject, every project or topic, should have a forum associated with it. I'd like to think that this could work at Higher, Further and Secondary school level (Key stage 3 onwards, ie 11 years old +) and increasingly also at Key stage two (7 to 11 years of age).

So, what advantages would having an online discussion forum bring? First of all, the discussion forum would be open to all learners, including those who might be absent at the time of the actual session and any who needed to access the session remotely. This would mean that all learners could pose their questions on the forum and feel disadvantaged because they might have been unable to attend the session.

Questions can be posted to the forum at any time, so learners doing homework, coursework or revision could pose questions as and when they occur.

Questions and answers can be shared among all learners. In a lesson, a teacher might respond to an inbridual learner's question singly (i.e. giving only that learner a response) not knowing that others may also require the same answer, on a discussion board the response is available for all who need it.

A question need not be only asked of the teacher/lecturer but can also be asked of other learners. Other learners can also give their response to questions; this might have some appeal as it could mean that the teacher does not always have to be on hand to supply the answers. It also affords an opportunity for other learners to demonstrate their learning.

There is an added bonus in that each time the forum is added to; it becomes a resource which can be used in follow up sessions this year or in subsequent years.

We have to acknowledge that discussion forums are not perfect. They can be abused, some people may tend to dominate discussions and some are reluctant to make posts. However with only a simple level of monitoring, moderation and encouragement, an online forum can become a very effective tool and future learning resource.

Doug Woods http://dougwoods.co.uk/blog says:

I'm a former teacher who's always been passionate and enthusiastic about ICT in education. I now style myself as an ICT in Education Consultant and Trainer, a role has afforded me opportunities to work in new areas of educational ICT for both public and commercial sectors. I have a keen interest in ICT for SEN learning, inclusion and for transforming learning.

This article first appeared in Computers in Classrooms, the free e-newsletter for ICT/ed tech teachers and subject leaders. Please see this article for details of three great prizes to be given away to subscribers. The next issue will be a games-based learning special.

The Importance of Mobile Phones in Education

Teenager Ethan Davids describes how essential his phone is to him.

EthanFrom listening to music, to taking and editing pictures of teachers, the young community have found various ways to misuse the new technology being made available to them in such small and compact mobile phones. Obviously, anything that can disrupt learning, or teaching, cannot be accepted in a classroom environment and should be dealt with accordingly. It is my opinion that as technology advances at such a blistering pace, policies such as ‘mobile phones should be switched off and in your bag’, can be modified to benefit not only students, but teachers and schools alike.

As a student who has experienced some very rowdy and distracting classes, I know that mobile phones can cause huge distractions for not only students, but teachers as well. I am also aware that mobile phones can be a danger to the school environment; however I believe they can still have their benefits in the classroom.

As a very proud owner of an Apple iPhone 3G, I could rave all day about the importance of my mobile phone. It keeps me in contact wherever I go, which not only gives me peace of mind, but also my parents! An argument I have never understood is that youngsters have become too reliant on their mobiles. Nowadays mobile phones can be as useful to people as a pencil and paper, and I have never come across an argument that adults have become too reliant on those!

The ability to download ‘apps’ to phones such as the iPhone can also make it not only personalised, but useful for people in most situations. From word processing software to a program that keeps an eye on the stock market, the range of potential uses can just not be argued with. For example, instead of waking up tired and grumpy, I use an advanced alarm clock to measure my sleeping patterns which also wakes me up when I am sleeping at my lightest. Not entirely necessary, but this could still be beneficial to anybody!

So if this level of technology can benefit from city workers to journalists, why can it not be taken advantage of at school? I have numerously thought to myself in lessons such as Spanish and English that if it was accepted for me to use my phone, my learning could be improved. Instead of taking out a dictionary, I could simply use my translator, and instead of trawling through books for a piece of literature, I could find the book online and be directed to a specific word, and so on. The fact is that these phones are really just computers, yet I am unaware of a school that is reluctant to allow the use of these.

I'm not naïve; firstly not everybody has such an advanced phone and secondly, there are bound to be people who will take advantage. But as technology becomes cheaper, more people will invest in this equipment, and surely the people who take advantage of the leniency would use their phone regardless of new measures?

Schools themselves are modernising greatly. My present school, for instance, is in the process of becoming an academy. This means that from September 2010 it will no longer be classed as a ‘school’, and by 2013 it hopes to have established completely new buildings. I am part of a group of students who have listened to the new plans, and I was impressed with the new technology being considered. Ideas such as giving each student a laptop and registering attendance online are being planned already. I think it is fantastic that schools are finally ‘getting with the times’ and are understanding the importance of ICT in education! Eventually I hope mobile phones will be looked upon in a much more reasonable way and take a more important role in education. After all, there’s only so much fun you can have with editing teachers’ faces!

Ethan is a Year 11 (17 years old) student who is currently preparing for his final GCSE (High School graduation) exams. He is a huge lover of football, and Manchester United. He hopes to carry on his education to university where he hopes to study Law and French.

This is a slightly amended version of an article which first appeared in Computers in Classrooms, the free e-newsletter. The next issue is a games-based learning special, and we're running a prize draw to give away 2 marvellous prizes. More on that later today.

Your newsletter editor is hard at work sifting through the submissions for Digital Education, the free newsletter for education professionals. Have you subscribed yet?

Read more about it, and subscribe, on the Newsletter page of the ICT in Education website.

We use a double opt-in system, and you won’t get spammed.

Review of Marxio

Update: Marxio appears to be no longer available, and I am trying TimeLeft instead (see bottom of article for link). You may, of course, wish to read this review anyway for its erudition and general insightfulness :-)

If you're anything like me, time is always at a premium. But relying on the clock in the toolbar isn't always effective as a way of keeping you on track. There’s a pretty good timer from Marxio. I set it to remind me to take a break every 20 minutes. (I often ignore it, but that’s another matter.) Obviously, you could use it to set a time limit for reading, or writing, or anything else.

Timely reminders

Timely remindersAs you can probably tell from the screenshot, there’s a wealth of options. And it’s free! Download it from the Marxio website, where you can see a list of features.

I quite like it, although I haven't used it for a while. I especially like the fact that you can configure your own settings, such as the text of the reminder and when it appears, and save them as a "schema". Why not give it a whirl?

This is a slightly amended version of an article that first appeared in Computers in Classrooms, the free newsletter about educational ICT.

Blast! I just tried to re-download Marxio and it seems to have disappeared. I am now trying out TimeLeft instead.

How To Start Blogging

Get writing!You know when a theme is developing in your life when the same sort of thing keeps cropping up. Well, I don’t know if twice in succession qualifies, but I’m going to go with it anyway. Yesterday I was catching up on my podcasts, and listened to a Grammar Girl episode entitled “How to get started blogging”. Then today I ran my blogarizer spreadsheet and was directed to an article entitled “10 must-use tips for beginning bloggers”. OK, enough already: I can take a hint.

Get writing!You know when a theme is developing in your life when the same sort of thing keeps cropping up. Well, I don’t know if twice in succession qualifies, but I’m going to go with it anyway. Yesterday I was catching up on my podcasts, and listened to a Grammar Girl episode entitled “How to get started blogging”. Then today I ran my blogarizer spreadsheet and was directed to an article entitled “10 must-use tips for beginning bloggers”. OK, enough already: I can take a hint.

Both articles are pretty good, in a general sense. Mignon Fogarty, the “Grammar Girl”, deals with knowing your audience, finding good, and reliable, information, and how to build your audience. Melissa Tamura, author of the 10 tips post, also talks about knowing your audience and, in essence, how to grow it.

I’d like to come at this from a different angle or, to be more precise, to emphasise different aspects of blogging. Here goes:

- Start blogging. That’s right, just start. Stop navel-gazing, second-guessing the universe and playing “what-if?” games. Just start. Creating a new blog in something like Blogger takes all of five minutes. In fact, the most difficult part is thinking of a witty and memorable name.

- Definitely define your audience, but start with yourself. What I mean by that is, write the kind of articles that you would find most interesting/enjoyable/useful to read. Then your blog will probably go one of two ways: either extremely eclectic, which stands a good chance of attracting a wide variety of people, or extremely focussed. Those two are not mutually exclusive, by the way. I think that latter possibility warrants a bullet point of its own…

- Be extremely focussed. I mean extremely focussed. From time to time I receive comments from people along the lines of they have nothing unique to blog about. That’s plain wrong, because everyone is unique in some way. For example, you might be the only art teacher in your town who takes their class on a virtual art gallery tour every week. How does that work? How does a virtual gallery visit stack up against a real life one? I don’t know from first-hand experience what the answers to these questions are. But you do.

- Put your audience first. I think if you’re going to write for an audience, you should at least try to make reading your work a pleasant experience. This is all highly personal and subjective, of course, but for me the two things I really can’t abide is swearing or implied swearing, and writing which is about as interesting as the list of ingredients on a packet of cornflakes. There’s no need for the former, and you can improve on the latter by analysing what it is you like about the writing of the blogs, magazines, newspapers, authors you read on a regular basis.

But the most important one of these, if you’ve decided or almost decided to start your own blog is the first one: just do it!

Related articles by Zemanta

Does ICT Improve Learning?

The intuitive answer to those of us involved in ICT is “of course it does”. However, the evidence from research is not conclusive. I think the reason is that it’s actually very difficult to carry out robust research in this area. As the impact of ICT has been a topic for discussion recently in the Naace and Mirandanet mailing lists, I thought it might be useful to try and clarify the issues as I see them.

The question “Does ICT improve learning?” naturally leads on to a set of other questions that need to be addressed:

What ICT?

The question as stated is too broad. A computer is not the same as a suite of computers. It’s not even the same as a laptop, which is not the same as a handheld device. Software is not the same as hardware, and generic software, such as a spreadsheet, is not the same as specific applications, such as maths tuition software.

What other factors are present?

ICT doesn’t happen in a vacuum. What is the environment in which the technology is being used? How is the lesson being conducted? What is the level of technical expertise of the teacher? What is the level of teaching expertise of the teacher? These and other factors mentioned in this article are not stand-alone either: they interact with each other to produce a complex set of circumstances.

What is the ICT being used for?

What is being taught? There is some evidence to suggest that computers are used for low-level and boring tasks like word processing, in which case comparing technology-“rich” lessons with non-technology-rich lessons is not comparing like with like. On the other hand, technology can be, and often is, used to facilitate exploration and discussion. Since these are educationally-beneficial techniques in their own right, the matter of validity needs to be scrutinised (see below).

How is the impact of the ICT being evaluated?

There are several ways in which this might be done, each with their own advantages and disadvantages. For example, in-depth case studies yield rich data but may be difficult to generalise from. Also, there are three other problems. One is that it is difficult to conduct experiments using a suitable control group, because no teacher wishes to try something which may disadvantage a particular group of students. Another is the so-called “starry night” effect, in which case studies focus (naturally) on the successful projects whilst ignoring all the ones which either failed or were not believed to have deliver the same level of benefits. Finally, there is the danger of all kinds of evaluation study, that the methodology itself may affect the outcome.

What exactly is being measured?

This is the issue of validity, already touched upon. Are we measuring the ability of a teacher to conduct a technology-rich lesson, in which case it’s the effectiveness of the teacher rather than the ICT that is being weighed up? By implication, it may be the quality and quantity of professional development which is being measured. It may be students’ home environments that are inadvertently being evaluated, or student-staff relationships.

How much is ICT being used?

I suggest there may be a difference between schools in which ICT is being used more or less everywhere, and those in which it’s hardly being used at all. In the former, presumably both teachers and students would be accustomed to using it, there would be a good explicit support structure in the form of technical support and professional development, and a sound hidden support structure in the form of being able to discuss ideas with colleagues over lunch or a cup of coffee.

Is there an experimenter effect going on?

This is the phenomenon whereby the results of a study confirm or tie in with the expectations of the people or organisation responsible for the study. This is an unconscious process, not a deliberate attempt to cheat. I’ve explained it in my article called Is Plagiarism Really a Problem?

Conclusion

My own feeling – backed up by experience -- is that in the right set of circumstances, the use of ICT can lead to profound learning gains. However, rather than falling into the trap of arguing whether ICT is “good” or “bad”, we need to move the debate onto a much sounder intellectual basis.

Further reading

I’d highly recommend Rachel M. Pilkington, “Measuring the Impact of Information Technology on Students’ Learning”, in The International Handbook of Information Technology in Primary and Secondary Education, Springer, 2008, USA.

What are the big issues facing ICT (Ed Tech) leaders? Please take a very short survey to help us find out.

Assessing ICT Understanding

I always have the impression – I know not why – that people who educate their children at home (known as “homeschoolers” in the USA) are somehow not regarded as “proper” teachers. Yet if you think about it, they potentially have much less of a support network than teachers in a school, and less guidance on how to do things. If I am correct in such sweeping assumptions, perhaps there is something the rest of us can learn from them in certain areas? I mean, if they have had to do a lot of figuring things out for themselves, to find out what works and what doesn’t work in their particular context, it would be a wasted opportunity to not benefit from that in some way.

A case in point is assessing youngsters’ understanding of ICT. It’s a notoriously difficult thing to do. Without going into a lot of detail now (see this article for more, although it needs some updating), the chief issues are the following:

- Is the assessment valid, ie does it measure what it purports to measure? You could be measuring literacy, for instance.

- Is it reliable? That is, if you applied the same test to similar pupils elsewhere, or the same pupils tomorrow, would the results come out more or less the same?

- Are you assessing the pupil’s own work, or a joint effort? How do you know what the pupil has done by themselves?

- The nature of the assessment can itself affect the result. If the pupils have learnt something using technology, testing them with a pencil and paper test is not likely to be appropriate. It will almost certainly yield a different outcome than if you used technology for the assessment. Similarly, if the pupils have been learning through scenario/problem-based learning and are tested through multiple choice, there is likely to be a question about validity.

- Rubrics: I am not sure they are ever really valid, and think they tend to be either too “locked down” or not objective enough.

So I was interested to read Ashley Allain’s views on assessment. Ashley, a homeschooling mother of four who contributed two fantastic case studies to the Amazing Web 2.0 Projects Book says:

To coin a phrase from Howard Gardner, I want to know if our children are reaching a level of "genuine understanding". In other words, I want to see if they have moved beyond basic mastery of the material towards a deeper, richer level of understanding.

This resonates with me. I sometimes meet people who know a lot of stuff and yet have no clue how to apply their knowledge in a real situation. It’s as if they know, but do not truly understand.

Ashley goes on to say that the usual sort of testing regime had unfortunate side effects:

As a matter of fact, our then second-grader, directly associated her daily mood with how well she performed on a given test.

As a consequence,

We take a more organic approach versus a rigid, test-driven curriculum. Assessment is often done through formal discussions, projects, and portfolios.

Have the pupils fared badly in compulsory tests? Quite the opposite. Ashley’s inspiring post (do go to it and read it in its entirety) suggests that if you can drag yourself away from checkboxes, point scores and all the rest of it, assessment can be both enjoyable and reasonably accurate.

The Power of Words

The accepted wisdom is that when teaching a topic you should display a list of words associated with the topic – especially when first introducing it. Why? To my mind, words are representations of concepts, so if you have no idea what the underlying concept is, the word itself is surely meaningless? Before anyone can learn terminology, they need mental hooks on which to hang the words.

However, there is no doubt that we need to ensure that pupils and students do understand, and use correctly, the appropriate terminology for a given topic. One way of testing their understanding, and giving you an insight into any misunderstandings, is to try a fiction approach.

When I was teaching, I used to make up short stories in which the terms relevant to the topic being taught were used. The students’ task was to identify the words and then decide if they had been used appropriately. I never actually used terminology wrongly, in case I inadvertently reinforced a misconception they already had. By “inappropriate use” I mean suggesting something which, though not wrong exactly, could be questioned. For example, the story might include a scene in which someone creates a list of names for badges using a word processor. Of course you can do that, but if you have a large list of names, and you want to apply criteria such as printing out girls’ and boys’ names separately, a word processor is unlikely to be the most appropriate tool.

I liked that idea, and it worked well. But yesterday I came across an idea which turns that one on its head: get the kids to write the story. The original idea may be found at Creative Copy Challenge. Intended as a means of stimulating the creative juices of (fiction) writers, the site mainly puts up lists of ten words selected randomly, your task being to work them into a story. It’s challenging, fun (in a masochistic kind of way), stories submitted by people are great to read, and the comments on the posts by Shane Arthur are kind. (To give full credit, I came across the site via an article by Ali Hale called The Secret to Writing Powerful Words, at the Men With Pens site.)

OK, so here is my variation on the theme. At a suitable point during the teaching of a topic, or at the end, give the pupils a list of 5 to 10 words which relate to the topic – the words that you would normally put on the whiteboard or wall as a glossary aid-memoire anyway, and ask them to construct a short story, how-to guide, script for a 30 second TV advert or whatever. If you have a class blog, do what they do over at Creative Copy Challenge, which is to post the words as an article, and ask readers to submit their stories as comments. That way everyone gets to see everyone else’s efforts, which paves the way, in an educational context, for an interesting class discussion and some peer assessment. A further variation would be to have the kids working on the assignment in small groups or pairs. Incidentally, you don’t have to use a blog: any means of collaborative writing will do, and as far as I know all Learning Platforms have such a facility.

I think that would be a great way of testing the kids’ understanding and, as I suggest, for you to gain insight into how they’re thinking, but in an enjoyable way. But don’t take my word for it. Pop over to the Creative Copy Challenge website and have a go yourself. Then decide if it might work in your classroom.