#BloggersCircle In a recent address called 'What is education for?' to the Royal Society of Arts, Michael Gove bemoaned the fact that there is no government department in the UK whose sole remit is the pursuit of educational standards.

According to Gove, education is not regarded as a good enough end in itself, but as something which can help to achieve some other goal.

In his exposition of his views in favour of liberal education, he used the term 'the tyranny of relevance'. Although he wasn’t talking about Information and Communications Technology (ICT), this phrase did strike a chord with me. In the continuing debate over whether ICT should be taught as a subject in its own right, is there perhaps too much store set by 'relevance'?

I’ve noticed (although, curiously, I’d never consciously noticed it before) that whenever people tell me that they think ICT should be taught through the context of other subjects, they always cite 'relevance' as a factor. They almost always throw in a reference to kids having to suffer boring lessons on spreadsheets and databases. They seem to think that having lots of lessons on e-safety and plenty of opportunities to use blogs, Google and Wikipedia will somehow turn out youngsters who can use their knowledge of technology and ability to transfer their skills to excel in subjects right across the board.

Perhaps I have overstated my case slightly – but only slightly. Like Gove, I happen to think that the best kind of education is one in which students develop a deep knowledge of subjects. I like the idea of cross-curricular themes, and of making subjects 'relevant' both to each other and a wide range of issues and circumstances. However, I do not think you can achieve that without mastering individual subjects. To summarise, I regard the following statements (which are mine, not Gove’s) as axiomatic:

- It is important for students to gain a deep knowledge of ICT, because only by understanding key issues (such as the difference between data and information) can they protect themselves against some forms of hype.

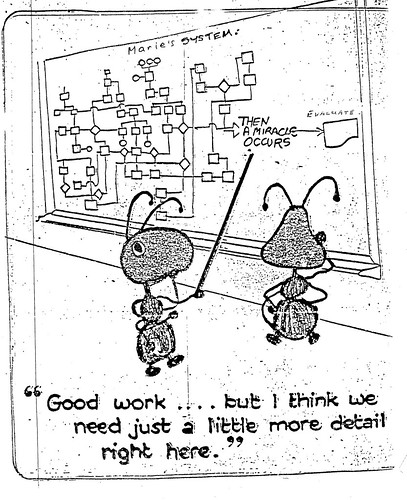

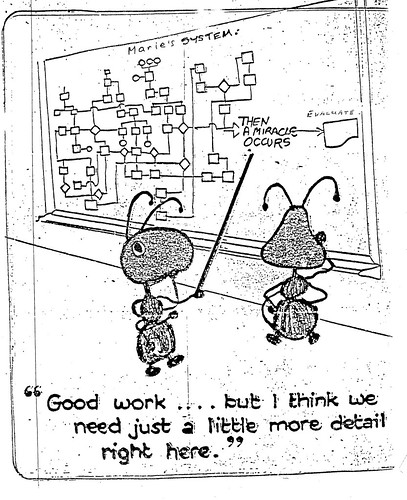

More positively, an understanding of how ICT can be used for 'provisional' activities, such as drafting and modelling, and an ability to appreciate the importance of precision in language (as required, for example, in 'sequencing' or programming, is essential for being able to avoid being subservient to a computer system’s apparent will.

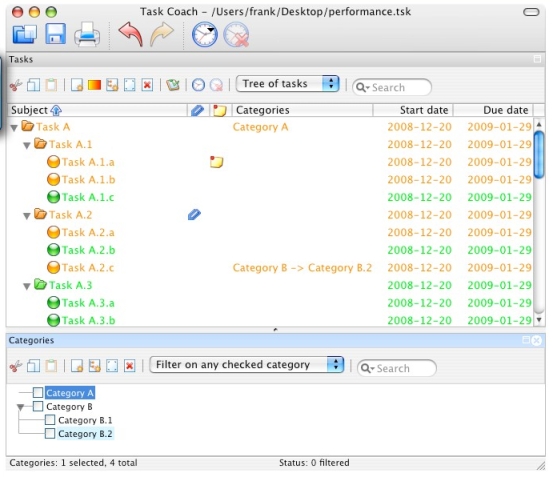

However, even this is falling into the trap of looking for 'relevance'. Why can't ICT be studied and enjoyed for its own sake? - Far from being boring, spreadsheets and databases can be extremely interesting, even beautiful. I don’t mean just to look at, but in their design and construction.

- Any teacher who makes spreadsheet or database lessons boring either has not had the time to develop interesting lessons, or does not really have a deep grasp of, and appreciation for, these areas themselves.

- What we need are teachers who have a deep love of ICT. I think to achieve that we have to encourage teachers to join communities in which important subject-related (not necessarily education-related) issues are debated (such as the RSA or British Computer Society).

- To help promote #4 we need to ensure that teachers have the time, and the authority, to develop teaching resources of their own.

- As part of that, teachers should have the flexibility to be able to teach topics they have a deep interest in.When I started teaching economics, something I was especially interested in was road pricing. I usually spent around 2 weeks on that topic alone, but in doing so I was able to touch on a whole plethora of concepts that I knew would prove relevant throughout the rest of the course.

- Finally, there needs to be an entitlement for top quality professional development, and the funds to back it up. For example, why shouldn’t teachers be able to apply for a ‘scholarship’ to attend national or even international conferences about educational technology?

I strongly believe that if we are to tackle the oft-cited lack of computer programming courses, say, or the sometimes perceived 'dumbing down' of ICT as a subject in its own right, we have to address the 'tyranny of relevance'.

The video of Michael Gove’s talk may be viewed on the RSA website.

This article was first published on 2nd July 2009.