“The central thesis is powerful and backed up by a breathtaking array of examples”

Here is a very strange paradox. On the one hand, everyone agrees that a key ingredient for success in life is having great teachers. On the other, there’s a relentless narrative that education is somehow broken and that fixing it entails replacing teachers or transforming some or all of what they do.

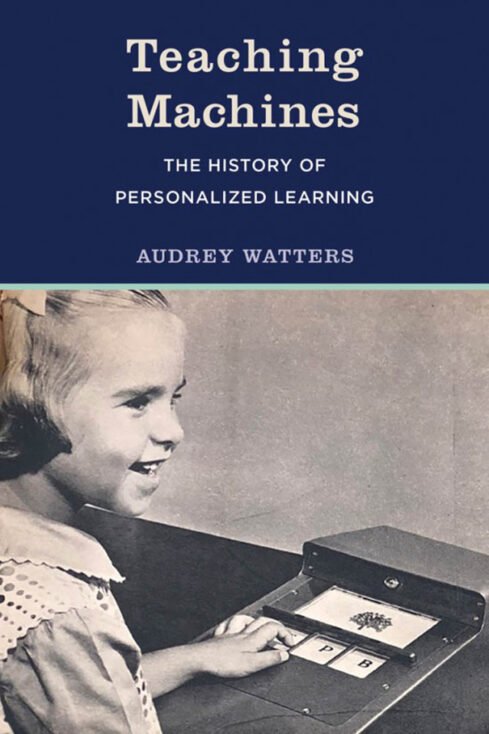

Teaching Machines deals with the development of technologies to effect the latter, and while its sole focus is the United States, it provides invaluable insight into the mindsets of the sort of people behind them. People who believe that education needs rescuing, and have the messianic zeal to believe they are the ones to rescue it.

The issues it focuses on are just as relevant here. Take our erstwhile Key Stage 3 Strategy, for example. It didn’t involve teaching machines, but, rather, took the novel approach of effectively turning teachers into machines with lessons that weren’t exactly scripted but didn’t fall far short. Twenty years on, some MATs use fully scripted lessons today.

Not that we’ve been altogether immune from attempts to mechanise teaching either. It’s not so long ago that computer programs first purported – falsely, according to two independent research reports at the time – to offer instruction adapted to the needs of each individual. How many apps today continue to make that claim, now with AI as their selling point?

Some of these aims are laudable, which Watters recognises. Freeing teachers from mundane, onerous tasks such as checking basic subject knowledge is a notable one. Look behind the spin, though, and it becomes clear that such ‘teaching machines’ are really just ‘testing machines’. And while their effective use could enable teachers to be more creative and to spend more quality time with their students, they aren’t without their own ethical problems. AI programming, for example, is notoriously subject to incorporating the programmer’s biases – and these are seldom teachers.

The idea that schools are inefficient is renewed by each generation of ‘disruptors’

And as Watters astutely notes, all of this happens in a cultural context that is often ignored or taken for granted. The idea that schools and teachers are inefficient is renewed by each generation of what we now call ‘disruptors’. It was used to justify the application of Taylorism or ‘scientific management’ to education (cf. league tables and Ofsted). And each time based on a fear that we are falling behind internationally.

“Too often,” Watters says. “the context is stripped [out] and all that seems to matter is the technology itself. Its history is simply a list of technological developments with no recognition that other events occurred, that other forces (cultural, institutional, political, economic, and so on) were at play.”

Sal Khan is a case in point. His suggestion that internet video-based instruction could reinvent education, Watters shows, is merely a repeat of similar claims made for film, radio and television. Yet education has come to incorporate all of these, demonstrating its ability to change and adapt. So while his accusation that education has not fundamentally changed in hundreds of years generates national headlines, the main contention of Teaching Machines is that he is only the latest in a long line of those making such claims. In fact, according to Watters, it is this thinking that hasn’t changed for over a century.

In short, Watters’ central thesis is a powerful one, and Teaching Machines provides a breath-taking array of examples to back it up.

However, that sheer amount of detail is one of the book’s key drawbacks. So much so that I’m tempted to suggest that a second edition should focus on the chapters about programmed instruction and relegate most of the rest to a voluminous notes section at the back.

And while it is highly readable for the most part, Watters relies too often on loaded language that does little to enhance her narrative. Presenting those she criticises as “sneering”, “scoffing” or “crowing” is just as likely to turn some readers off.

Notwithstanding these quibbles, however, this is a well-researched and important book that should be on every educationalist’s reading list.

This review first appeared in Schools Week.